|

| A Mighty Citadel by J. Humphries on Deviantart |

I say D&D, although I mean specifically BECMI/RC. The mechanics on building castles are pretty straightforward in the Rules Cyclopedia. See pages 135-139. They cover the gold needed and the approximate time to build free-standing structures, as well as dungeons. They go into some detail about finishing touches and staffing. Rules do cover the cost of troops and retainers in line with the absurd price ranges prevailing in fantasy D&D games. After all, there is no hard limit on the number of times PCs can ransack fabulous dragon hoards to afford all this, other than the Dungeon Masters’ agencies. This article is not about reinventing the wheel. It focuses instead on the cost of upkeep.

Starting Point: I read an article about Henry Algernon Percy’s budget for Alnwick Castle in Northumberland (Medieval World magazine, Issue #14). It lists noteworthy expenses, somewhat incompletely. Things to consider include food, beverages (local or imported), fuel (wood, coal, charcoal, and perhaps oil, peat, or cow dung), cooking ingredients, condiments, and spices, tools and goods, linen, clothing, and other cloth items (and how they are cleaned), regular facilities maintenance, staffing, etc. I won't delve into a lengthy list of individual costs. The RC’s minutia on building castles already involves quite a bit of bookkeeping, so I’ll skip all that and focus on what matters: a quantifiable average cost.

Unequal Values: I have conflicting data at hand: real-world values in Pound Sterling and other currencies (which vary with century and location) vs. the inflated D&D price structure. There’s no perfect way to reconcile reliably five centuries of economic reality with a single fantasy world. This is my disclaimer that what follows is not meant to be scientific or historical, but rather a simple set of mechanics that work with established D&D rules.

Location: The RC addresses three different regional aspects: Wilderness, Borderland, and Settled. This will affect operating costs in different ways.

- Wilderness: The problem here lies in what goods and services are available locally. Odds are, common supplies and services other than what the garrison can provide have to be brought in overland, by sea and/or river, or on skyships if available at all, since there are no villages or farms to honor feudal dues. Therefore, most of these services and goods have to be paid for in cash.

- Borderland: Feudal dues collected from villagers and farmers living nearby cover part of the cost of goods and services. This reduces the need for hard cash. Some finer goods and materials will still have to be purchased and transported from large towns and cities, some good distance away in settled regions. For example: glassware, window panes, fine woods, condiments, spices, finer beverages, affluent clothing, tapestries, incense, ink, scrolls, books, healing medications, perfumes, etc. Along the way, storms at sea, piracy, road banditry, graft, and other shenanigans will have to be contended with.

- Settled: Most common goods and services come as feudal dues from abundant local sources. Nearby urban centers, ports, and seasonal fairs permit easier access to sophisticated goods and more readily attract a skilled workforce. In other words, the need for hard cash to operate identical fortifications should be lowest in settled areas vs. total wilderness.

Function: Another factor is the castle’s status. Is it a military outpost (rough and basic, if not downright crude)? A provincial stronghold (the appanage of a knight, a baron, a high-ranking ecclesiastic, or a magic-user)? The fortified dwelling of a wealthy and influential aristocrat, if not a royal castle, frequently sponsoring festivals, holding jousts, hosting costly banquets, and housing notable guests? Evidently, the latter won’t exist in a wilderness.

Social Standing: Based on usage, a simple military stronghold will be inherently cheaper to operate compared to the fortified dwelling of a wealthy aristocrat involving much more sophisticated goods and services. Garrisons are not included here since game rules directly establish the cost of troops, specialists, and higher-ranking retainers. On the other hand, the operating costs listed below do include common staff possibly residing on site, such as pages, cooks, bakers, butchers, a stable master, grooms, clerks, a chaplain and low-ranking members of the clergy, nursemaids, chambermaids, carpenters, masons, blacksmiths, falconers, musicians, jesters, gardeners, cleaners, porters (breathe here and hold your breath), stinky gong farmers (if you know, you know), etc. An outpost would have very few of these people, if any at all, while a wealthy estate could count many. Repairing regular wear and tear is also included here as opposed to damage resulting from battles, monster attacks, and natural disasters.

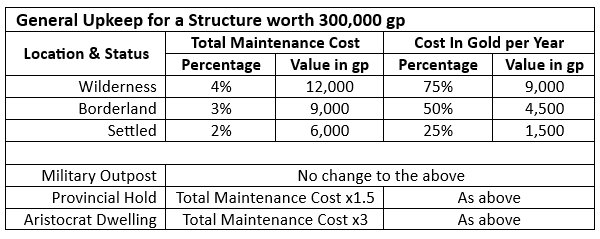

Figuring Numbers: I think the simplest approach is to base general upkeep on percentages of the original cost of building the structure. Total Maintenance Cost includes the value of feudal dues (local goods and services) provided by local inhabitants and gold payments for what isn’t locally available. The Cost in Gold is the part of the Total Maintenance Cost that the castle’s owner must pay in cash over a calendar year. The latter does not include any interest on loans, royal levies, tithes, or scutage fees the castle’s owner must pay to a liege. The cost of feeding garrisons should be covered in the RC’s rules, and therefore does not figure in the chart below.

Basis for Comparison: I picked 300,000 gp as a basis for a structure comprising a square keep, four towers, connecting walls, a barbican, a gatehouse, a few stone buildings, and perhaps a small dungeon (see RC page 137). This enables a fair comparison of the same structure across the board.

Size Considerations: A provincial stronghold’s estate should be more elaborate than a simpler military outpost, easily costing twice as much to build. A Google search (with unconfirmed results) priced the upkeep of a 15th-century Scottish lord’s castle at £800 per year, a substantial sum in those times. I’m assuming that’s the Total Maintenance Cost, including the relative value of feudal services. To reverse engineer this amount, I’m using the following conversion rate: £1 = 80 real-world silver pennies. As a result of D&D cost inflation, however, I’d rather set the conversion rate at £1 = 240 D&D silver pieces instead of 80 (a 3 to 1 ratio). Thus, £800 x 24 D&D gold pieces adds up to a Total Maintenance Cost of 19,200 gp yearly, of which 800 gp per month are paid in cash. This matches the Total Maintenance Cost for a borderland provincial hold about twice the size of the one suggested in the upkeep table above. Original building costs would have been 300,000 x 19,200 / 9,000 = 610,000 gp. This would include additional towers and walls surrounding the local town, an expanded great hall, family living quarters, a temple, a substantial granary, some paving, arts and decorations, etc.

Cutting Costs: A very basic wilderness outpost with a simple stone keep and a few adjoining buildings could cost about 100,000 gp to build rather than 300,000 gp. Its upkeep (without the cost of troops) would be 4,000 gp yearly, of which 250 gp must be paid in cash each month. The same keep in settled lands would require about 40 gp cash per month since more people live nearby who can honor feudal dues—essentially free goods and services to their lord. It makes a great deal of sense for a lord to clear the surrounding land and attract inhabitants to improve its status from wilderness to borderland, and eventually to a settled area. Nearby hamlets and villages are a boon. According to a Google search, the upkeep for a 15th-century knight’s household forces could run about £30-£60 per year. This would amount to 60-120 D&D gold pieces per month for food, equipment, lodging, and armed services. Rank-and-file soldiery in the real world was paid quite a lot less than typical D&D retainers.

The Rich and Fabulous: Naturally, a fortified estate housing a wealthy and influential aristocrat, or a fantasy world’s royal fortress, may include sprawling facilities costing a great deal more than 300,000 gp to build, probably more like ten times as much. The upkeep for such extravagant property in a settled region could reach 3,750 gp paid in cash per month, aside from feudal goods and services. If I use the conversion rate listed earlier, this would amount to about 156 real-world pounds sterling per month. For reference, a medieval monarch’s personal income in 12th-century England historically ran £10,000-£20,000 per year, or somewhere around £800-£1,600 per month (uncorroborated Google search).

The Real World vs. Fantasy: Another quote I found was for constructing Conwy Castle in the 13th Century. Records (unconfirmed) show a cost of £15,000 or 360,000 fictitious D&D gold pieces. D&D-wise, this seems a bit cheap given Conwy’s footprint (see image). This includes very roughly a main keep, several extra buildings, 2 barbicans, 8 towers instead if 4, etc. Here’s the whole list: 1. Site of Drawbridge, 2. West Barbican, 3. South-West Tower, 4. Prison Tower, 5. Bakehouse Tower, 6. King's Tower, 7. Chapel Tower, 8. Stockhouse Tower, 9. Kitchen Tower, 10. North-West Tower 11. East Barbican, 12. Lesser Hall, 13. Great Hall, 14. Chapel, 15. Site of Kitchen & Stables, 16. Site of Granary. Using the RC’s construction guidelines, this would probably cost more than 400,000 gp, not including the 14th-century outer walls protecting the town of Conwy.

I’m not sure if 13th-century Wales should be considered a borderland or a settled area. After all, there was a Cistercian monastery on site, which was rebuilt upriver. As far as I know, the village of Conwy was built soon after the castle’s construction to attract English settlers. That’s definitely in line with the game’s suggested strategy. Although it is officially deemed a royal castle, it is primarily a military fortress rather than a permanent dwelling for a king and his retinue, like the way Windsor Castle looks today, for example. This may qualify more as a large provincial stronghold, as defined in this article. There is some leeway as far as status goes.

Here is the full layout of Conwy Castle with its 14th-century outer walls and defensive ditch protecting the town. Click here to read the castle’s complete history.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.